Preparing and Testing for a Live Streaming Show

Author: John Wilson

[email protected]

Date: February 17, 2021

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Ottawa Jazz Happenings or of JazzWorks Canada.

1.0 Introduction

The purpose of this second article (see Note 1 below) is to share the logistical preparations undertaken for Cuppa Joe’s Facebook Live show on December 15th, 2020, and some of the technical issues that needed addressing in order to stream the concert successfully, given the equipment we were using.

Since we were new to live streaming, we spent a fair bit of time early on making sure our show would be a success. We knew that we had equipment not often used in live streaming, due to the need for a mixer to blend our four voices. But we also wanted to keep the tradition of our usual live shows, by making the staging interesting to viewers. In addition, since these shows were to be aired at night time, we wanted to be sure that — even socially-distanced — all four vocalists would be well-lit.

We were interested in the ability to download the recording of our live stream afterwards, in order to use clips of some of the songs for various other purposes. So we investigated how this could be done. And since we were using a cellphone as our main video camera — and tablets to monitor audience participation — we wanted to make sure that notifications from calls, texts, etc. wouldn’t interrupt the show, nor the recording of the live stream.

This article is organized in segments, to address these key areas of staging, lighting, testing, recording and technology.

Note 1: This is a companion to my more technically-focused first article about this live stream show, entitled “Live Streaming with a Mixer, a Computer, and Streaming Software”.

The purpose of this second article (see Note 1 below) is to share the logistical preparations undertaken for Cuppa Joe’s Facebook Live show on December 15th, 2020, and some of the technical issues that needed addressing in order to stream the concert successfully, given the equipment we were using.

Since we were new to live streaming, we spent a fair bit of time early on making sure our show would be a success. We knew that we had equipment not often used in live streaming, due to the need for a mixer to blend our four voices. But we also wanted to keep the tradition of our usual live shows, by making the staging interesting to viewers. In addition, since these shows were to be aired at night time, we wanted to be sure that — even socially-distanced — all four vocalists would be well-lit.

We were interested in the ability to download the recording of our live stream afterwards, in order to use clips of some of the songs for various other purposes. So we investigated how this could be done. And since we were using a cellphone as our main video camera — and tablets to monitor audience participation — we wanted to make sure that notifications from calls, texts, etc. wouldn’t interrupt the show, nor the recording of the live stream.

This article is organized in segments, to address these key areas of staging, lighting, testing, recording and technology.

Note 1: This is a companion to my more technically-focused first article about this live stream show, entitled “Live Streaming with a Mixer, a Computer, and Streaming Software”.

2.0 Staging

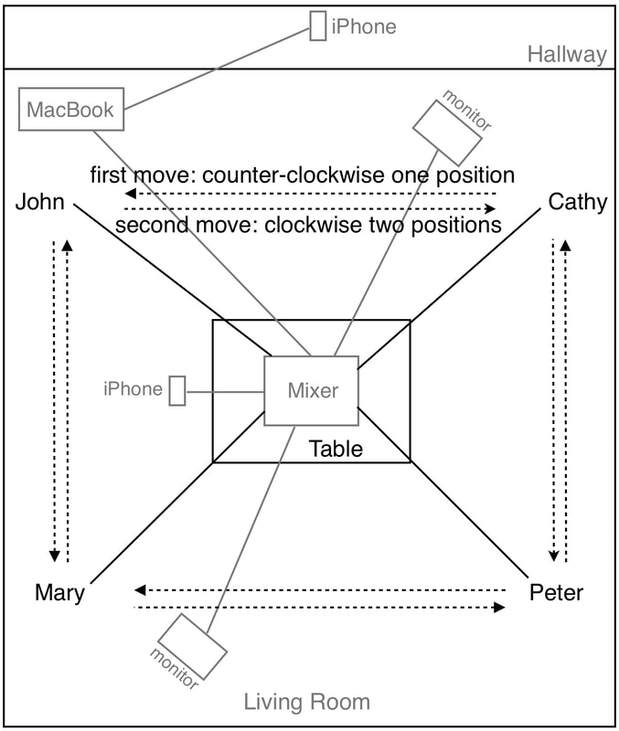

Cuppa Joe uses some simple stage choreography moves, along with dialogue, in our concerts. With COVID concerns and physical distancing, we could not do our usual schtick, so we came up with a “moving stage”. We had three setups that had us move from one to another simply by rotating through our “stations” clockwise and counter-clockwise (see Image 2.1). This achieved two objectives: making the staging more interesting, and putting those with solos or song introductions closest to the camera.

Cuppa Joe uses some simple stage choreography moves, along with dialogue, in our concerts. With COVID concerns and physical distancing, we could not do our usual schtick, so we came up with a “moving stage”. We had three setups that had us move from one to another simply by rotating through our “stations” clockwise and counter-clockwise (see Image 2.1). This achieved two objectives: making the staging more interesting, and putting those with solos or song introductions closest to the camera.

Image 2.1 — Performance Space Arrangement

Due to COVID, our overriding concern was to minimize the number of stage moves, and to make sure we all moved together without the need to cross over one another. Since we have one person delegated to get our starting note, one person counting us in, and others introducing tunes, these moves also determined who would have the opportunity to check tablets (in our case: iPads) and acknowledge audience members as they arrived or commented to us about the show.

In the lead-up to its start, to let viewers know that they had reached the live stream, we used a simple chart taped to a music stand (see Image 2.2). To keep it as 'up-scale' as possible without too much cost, it consisted of one of our quartet photos with a few words about when the show would start (and a Christmas decoration). We had someone remove the music stand from in front of the camera when we were ready to begin; that way, we were set in our stations, ready to go, at the appointed time.

In the lead-up to its start, to let viewers know that they had reached the live stream, we used a simple chart taped to a music stand (see Image 2.2). To keep it as 'up-scale' as possible without too much cost, it consisted of one of our quartet photos with a few words about when the show would start (and a Christmas decoration). We had someone remove the music stand from in front of the camera when we were ready to begin; that way, we were set in our stations, ready to go, at the appointed time.

Image 2.2 — Live Stream "Waiting Room" Chart

3.0 Lighting

The Zolas live streams are at night, and ours was in mid-December when it was already fully dark when our show started. With four physically-distanced performers in a fairly large room, lighting became an important matter. The room’s usual lighting provides good reading light, but it’s mostly a yellowish tungsten cast and does not light a person’s face.

So we came up with additional high-temperature “key” lighting (see Note 2) that we installed behind the camera to provide front lighting on our faces — a light for each band member (see Image 3.1). The high-temperature lighting provides almost a daylight feel, giving us the look you’d expect at a concert venue. We also found that the chart with our photo attached — used before the show started — was in shadow, in front of the camera, so brought another “key-light" in to illuminate it.

Since we tested this setup a number of times, while we were sorting out some technical issues we found it useful to “spike-mark the floor”. We used painter’s tape to mark the locations of the feet of the camera tripod, the music stand with photo, and the various key lights, so we could set them up quickly each time.

Note 2: Key lighting refers to the primary light source for a staging situation, whether in photography, theatre, film, or TV. It is used to light the subject matter that is most important to the scene or situation. As a counter-example, fill light is secondary light that helps remove or reduce shadows in certain areas.

The Zolas live streams are at night, and ours was in mid-December when it was already fully dark when our show started. With four physically-distanced performers in a fairly large room, lighting became an important matter. The room’s usual lighting provides good reading light, but it’s mostly a yellowish tungsten cast and does not light a person’s face.

So we came up with additional high-temperature “key” lighting (see Note 2) that we installed behind the camera to provide front lighting on our faces — a light for each band member (see Image 3.1). The high-temperature lighting provides almost a daylight feel, giving us the look you’d expect at a concert venue. We also found that the chart with our photo attached — used before the show started — was in shadow, in front of the camera, so brought another “key-light" in to illuminate it.

Since we tested this setup a number of times, while we were sorting out some technical issues we found it useful to “spike-mark the floor”. We used painter’s tape to mark the locations of the feet of the camera tripod, the music stand with photo, and the various key lights, so we could set them up quickly each time.

Note 2: Key lighting refers to the primary light source for a staging situation, whether in photography, theatre, film, or TV. It is used to light the subject matter that is most important to the scene or situation. As a counter-example, fill light is secondary light that helps remove or reduce shadows in certain areas.

Image 3.1 — "Key" Lighting

4.0 Testing

We didn’t want to run into either a delayed start to the 7:00 pm show while fixing issues late in the game, or end up stopping the show to make adjustments that we could have sorted out beforehand. Either of these affect the flow of the show, and could possibly result in audience members leaving early.

Unlike an in-person show (remember those?), these live streams do not require the audience to purchase tickets, nor to commit to stay because they have travelled to a restaurant or other venue. So any kind of disruption — one that might be tolerated in-person while enjoying some food or a beverage with friends — could be disastrous. In addition, compared with the relaxed, convivial atmosphere of a venue, some people are watching live streams on a cellphone or a computer, perhaps by themselves, and not necessarily in their most comfortable surroundings nor seating. The separation from the audience via digital link makes communication “from the stage” about any problems or delays difficult or impossible, depending on the situation, should there be no sound (or video) reaching the audience.

Not really anticipating any particular difficulties in establishing a Facebook Live show, but wanting to be sure it ran smoothly, we started an equipment setup a few weeks in advance. (And, frankly, I enjoyed learning the technical aspects of setting up a live stream show.) The early testing was primarily to confirm everything would work with our new digital mixer, since many performers don’t use a mixer in their live stream setup.

That first, very simple, setup — shown in Image 6.1 — didn’t work. And this led to a lot of testing and trying out of different configurations, and discussions with our mixer manufacturer. You can read about the technical issues and solutions in my February 10th, 2021 JazzWorks article entitled “Live Streaming with a Mixer, a Computer and Streaming Software”. Suffice it to say, it took a while to narrow down the issue(s). Here I was, trying to hear the sound from the mixer-connected mic, before realizing that in my case, Facebook Live was not capable of picking up that sound via my iPhone; so all I was hearing was the sound from my iPhone’s internal mic.

Creating an invitation-based Facebook Group to use in testing out various options was helpful. The results could be seen immediately by other quartet members from their homes, and anyone else interested or helping to resolve the issues. It also created a visual record of the problems encountered, as different solutions were investigated and tried out. Recording to this group also helped to illustrate how the “stage” lighting would work, while trying out and comparing different options.

We used a phone as the camera, a computer to integrate inputs through streaming software, and iPads to monitor our show and interact with the audience. As a result, we were a bit concerned that equipment might be disrupted, or unwanted sounds or ringing might occur if any of these devices received a phone call, a text, a Facebook posting, a FaceTime call, etc. So we tested each of these scenarios.

It’s important to make sure that your notifications aren’t going to stop the show. The one that caused us the greatest concern was someone initiating a FaceTime call to my wife. She was in another room monitoring the event through her iPad, so she could advise us of any perceived problems, such as internet or Facebook Live connection issues. As long as she didn’t answer a FaceTime call, only her iPad would signal her. But if she answered it, the MacBook we were using to reach Facebook Live would also pop up a FaceTime window, complete with sound! Yes, that would interfere with the other application windows we had open with Facebook and with our streaming software!

One other important test involved moving the mp3 of the background music we would use prior to the show to a device that we could plug into our mixer, since that would be our sole audio source for the show. Although we could have played it into one of our mixer-connected mics, the sound quality wouldn’t be as high, and we might need to adjust the sound level of the mic for our show. This could cause some delay and interruption at the beginning, since we carefully balance the sound from our four voices through the mixer. There would also be the risk of forgetting to adjust the mic for the vocalist.

We didn’t want to run into either a delayed start to the 7:00 pm show while fixing issues late in the game, or end up stopping the show to make adjustments that we could have sorted out beforehand. Either of these affect the flow of the show, and could possibly result in audience members leaving early.

Unlike an in-person show (remember those?), these live streams do not require the audience to purchase tickets, nor to commit to stay because they have travelled to a restaurant or other venue. So any kind of disruption — one that might be tolerated in-person while enjoying some food or a beverage with friends — could be disastrous. In addition, compared with the relaxed, convivial atmosphere of a venue, some people are watching live streams on a cellphone or a computer, perhaps by themselves, and not necessarily in their most comfortable surroundings nor seating. The separation from the audience via digital link makes communication “from the stage” about any problems or delays difficult or impossible, depending on the situation, should there be no sound (or video) reaching the audience.

Not really anticipating any particular difficulties in establishing a Facebook Live show, but wanting to be sure it ran smoothly, we started an equipment setup a few weeks in advance. (And, frankly, I enjoyed learning the technical aspects of setting up a live stream show.) The early testing was primarily to confirm everything would work with our new digital mixer, since many performers don’t use a mixer in their live stream setup.

That first, very simple, setup — shown in Image 6.1 — didn’t work. And this led to a lot of testing and trying out of different configurations, and discussions with our mixer manufacturer. You can read about the technical issues and solutions in my February 10th, 2021 JazzWorks article entitled “Live Streaming with a Mixer, a Computer and Streaming Software”. Suffice it to say, it took a while to narrow down the issue(s). Here I was, trying to hear the sound from the mixer-connected mic, before realizing that in my case, Facebook Live was not capable of picking up that sound via my iPhone; so all I was hearing was the sound from my iPhone’s internal mic.

Creating an invitation-based Facebook Group to use in testing out various options was helpful. The results could be seen immediately by other quartet members from their homes, and anyone else interested or helping to resolve the issues. It also created a visual record of the problems encountered, as different solutions were investigated and tried out. Recording to this group also helped to illustrate how the “stage” lighting would work, while trying out and comparing different options.

We used a phone as the camera, a computer to integrate inputs through streaming software, and iPads to monitor our show and interact with the audience. As a result, we were a bit concerned that equipment might be disrupted, or unwanted sounds or ringing might occur if any of these devices received a phone call, a text, a Facebook posting, a FaceTime call, etc. So we tested each of these scenarios.

It’s important to make sure that your notifications aren’t going to stop the show. The one that caused us the greatest concern was someone initiating a FaceTime call to my wife. She was in another room monitoring the event through her iPad, so she could advise us of any perceived problems, such as internet or Facebook Live connection issues. As long as she didn’t answer a FaceTime call, only her iPad would signal her. But if she answered it, the MacBook we were using to reach Facebook Live would also pop up a FaceTime window, complete with sound! Yes, that would interfere with the other application windows we had open with Facebook and with our streaming software!

One other important test involved moving the mp3 of the background music we would use prior to the show to a device that we could plug into our mixer, since that would be our sole audio source for the show. Although we could have played it into one of our mixer-connected mics, the sound quality wouldn’t be as high, and we might need to adjust the sound level of the mic for our show. This could cause some delay and interruption at the beginning, since we carefully balance the sound from our four voices through the mixer. There would also be the risk of forgetting to adjust the mic for the vocalist.

5.0 Recording

When testing Facebook Live, we discovered that there were a number of options available, including trimming, clipping, and downloading the completed live streamed video. These options changed, based on a variety of factors which weren’t easy to pin down, but included whether you were starting from a “professional” Facebook page or a personal Facebook group. But these features appeared to be quite interesting and potentially useful.

Since we ended up using OBS streaming software on a computer to combine and deliver our audio and video to Facebook Live, OBS also recorded the result. But it did so with an unusual file format, which could only be opened via OBS. It turns out that you can set — via OBS preferences — the recording format to a variety of different file types, including the ever-popular mp4. Fortunately, for us, OBS had the ability to convert its default file format to a more standard one, such as mp4.

Later, while working on a music video for a client, we discovered that, although Facebook can record at 720p (see Note 3 below), it provides downloads at only 360p, which is a very low quality recording. Further investigation showed that, not only did OBS default to 720p, but at 60 fps (see Note 4 below) rather than Facebook’s 30 fps, providing a much better quality video. It turns out that OBS provides further quality improvement via its Preferences; so if you think you’ll want a recording of your event, set up those preferences in advance.

Note 3: Pixel count is a way of measuring video quality via its resolution, designated by stating the the number of pixels on the vertical axis of a frame (observed in a photo or video on a computer screen, phone, TV, etc.)

Note 4: "fps" refers to the number of frames of video recorded per second. The greater the number of frames, the better the perceived quality, since there is less transition noticed between frames.

When testing Facebook Live, we discovered that there were a number of options available, including trimming, clipping, and downloading the completed live streamed video. These options changed, based on a variety of factors which weren’t easy to pin down, but included whether you were starting from a “professional” Facebook page or a personal Facebook group. But these features appeared to be quite interesting and potentially useful.

Since we ended up using OBS streaming software on a computer to combine and deliver our audio and video to Facebook Live, OBS also recorded the result. But it did so with an unusual file format, which could only be opened via OBS. It turns out that you can set — via OBS preferences — the recording format to a variety of different file types, including the ever-popular mp4. Fortunately, for us, OBS had the ability to convert its default file format to a more standard one, such as mp4.

Later, while working on a music video for a client, we discovered that, although Facebook can record at 720p (see Note 3 below), it provides downloads at only 360p, which is a very low quality recording. Further investigation showed that, not only did OBS default to 720p, but at 60 fps (see Note 4 below) rather than Facebook’s 30 fps, providing a much better quality video. It turns out that OBS provides further quality improvement via its Preferences; so if you think you’ll want a recording of your event, set up those preferences in advance.

Note 3: Pixel count is a way of measuring video quality via its resolution, designated by stating the the number of pixels on the vertical axis of a frame (observed in a photo or video on a computer screen, phone, TV, etc.)

- Although the “p” means ”progressive scan”, 720p is commonly accepted nomenclature for 1280 (horizontal) pixels x 720 (vertical) pixels = 921,600 pixels in total.

- 360p refers to 640 x 360 = 230,400 pixels.

- 720p is actually 4 times the quality of 360p (921,600 pixels / 230,400 pixels).

Note 4: "fps" refers to the number of frames of video recorded per second. The greater the number of frames, the better the perceived quality, since there is less transition noticed between frames.

6.0 Technology

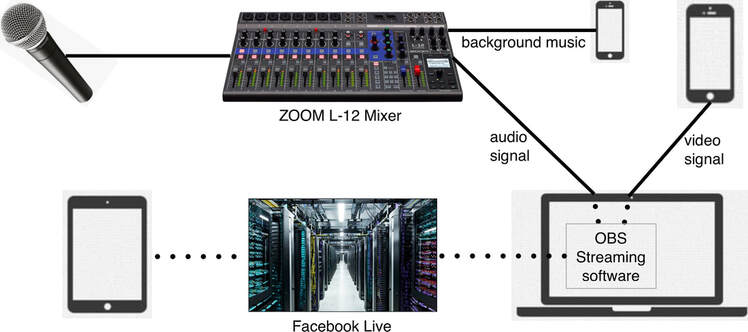

Image 6.1 illustrates the first test undertaken in preparing for our show (mentioned in section 4.0). A Shure SM58 mic is plugged into our ZOOM LiveTrak L-12 Mixer, which is connected to an iPhone X. The iPhone X is used to set up a Facebook Live session from the Cuppa Joe “professional” Facebook page, sending the results to the Facebook group page created for this testing arrangement.

Results were monitored via an iPad mini connected to that Facebook group page. The video portion captured by the iPhone was successfully recorded by Facebook Live into that Facebook group; however, the audio portion — from the mixer — was not.

Image 6.1 illustrates the first test undertaken in preparing for our show (mentioned in section 4.0). A Shure SM58 mic is plugged into our ZOOM LiveTrak L-12 Mixer, which is connected to an iPhone X. The iPhone X is used to set up a Facebook Live session from the Cuppa Joe “professional” Facebook page, sending the results to the Facebook group page created for this testing arrangement.

Results were monitored via an iPad mini connected to that Facebook group page. The video portion captured by the iPhone was successfully recorded by Facebook Live into that Facebook group; however, the audio portion — from the mixer — was not.

Image 6.1 — Initial Testing Arrangement

Once it was determined that the iPhone would not work as our sole interface to Facebook Live (you can read about the details in my February 10th, 2021 JazzWorks article entitled “Live Streaming with a Mixer, a Computer and Streaming Software”), it was clear that we’d need to use a computer. And, as described in that article, this meant separating the sources of the audio and video. As a result, we chose streaming software to run on the computer (a MacBook Pro), as shown in Image 6.2.

Image 6.2 — Final Testing Arrangement

This did not occur in a single step, but took much testing and consultation with others, again including the mixer manufacturer (who, by the way, provided excellent support, and someone was always available to discuss technical matters).

The decision to use OBS as an integrator of various inputs turned out to be a watershed moment in addressing the disparate sources of audio and video signals, because of the breadth of its functionality.

The key differences between the arrangement in Image 6.2 and our final setup for the show, are very simple: we moved to 4 mics connected to the mixer; we re-deployed the iPhone, which was providing early-on background music, to now give us our starting notes; and we had 3 iPads monitoring the live stream and supporting our interaction with the audience.

The decision to use OBS as an integrator of various inputs turned out to be a watershed moment in addressing the disparate sources of audio and video signals, because of the breadth of its functionality.

The key differences between the arrangement in Image 6.2 and our final setup for the show, are very simple: we moved to 4 mics connected to the mixer; we re-deployed the iPhone, which was providing early-on background music, to now give us our starting notes; and we had 3 iPads monitoring the live stream and supporting our interaction with the audience.

7.0 Rehearsing

This article is oriented towards preparation and testing, yet there’s been no mention of rehearsing, where most of the time is spent for a non-live stream show! We sure did lots of this, too. But this is normal, and requires little further discussion, as we all do it, and we do it in our own special ways, depending on the instrumentation, and the make-up of the band.

The article essentially covers the areas where I needed to prepare things in advance of rehearsals that involved all of the equipment mentioned and the rest of the band members.

This article is oriented towards preparation and testing, yet there’s been no mention of rehearsing, where most of the time is spent for a non-live stream show! We sure did lots of this, too. But this is normal, and requires little further discussion, as we all do it, and we do it in our own special ways, depending on the instrumentation, and the make-up of the band.

The article essentially covers the areas where I needed to prepare things in advance of rehearsals that involved all of the equipment mentioned and the rest of the band members.

8.0 Checklist

I found it a useful device to prepare a checklist, as I didn’t want to leave it to memory, then forget something, and have the show hiccup! The list included such configurations and settings as mixer balance and vocalist profiles, and OBS and Facebook Live preferences.

In addition, there were reminders about:

We even “tested” this checklist during our final couple of rehearsals leading up to the performance, to fine tune it.

I found it a useful device to prepare a checklist, as I didn’t want to leave it to memory, then forget something, and have the show hiccup! The list included such configurations and settings as mixer balance and vocalist profiles, and OBS and Facebook Live preferences.

In addition, there were reminders about:

- simple matters such as turning off the ringers of the landline phones in the house, and

- more significant matters like turning on the mixer’s audio recording, since it provides independent per channel recording of each (vocal) input.

We even “tested” this checklist during our final couple of rehearsals leading up to the performance, to fine tune it.

9.0 Conclusions

All of this planning, testing, and rehearsing resulted in a successful show. It attracted a large, diverse audience spanning the UK, Germany, Australia, the U.S., and Canada. In fact, within Canada, there were live viewers as far east as New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the Magdalen Islands, and as far west as Alberta. Attendance by people outside of the Ottawa area would not have been possible with a live in-person show at a local venue. This demonstrates the unique value of a live stream show. Live streaming should be considered for the post-COVID future, in addition to in-person shows. Cuppa Joe is certainly open to hosting or participating in such events.

The show went well, starting on time and running uninterrupted. There was just one hitch, which is worth sharing for others to consider in their shows. Despite all the testing, some audience members found the audio level too low, early on in the show. It was an easy fix to increase it from our mixer. But since we hadn’t anticipated a situation like this, we were not 100% sure which controls impacted the digital feed to the live stream. And increasing the overall volume caused the sound levels from our monitor speakers in the performance space to be louder than we are accustomed, making it more difficult to sing in our nuanced way and to hear and blend with one another as well. So we needed to adjust that volume back down a bit after a couple of songs; and that seemed to work for everyone.

The learning for us is to make sure we have split the mixer outputs for the monitor speakers from the controls for the digital feed, so they can be controlled independently. We also need to do more sound-level testing before the show, to ensure that we start at a volume level that is on the high side rather than the low side. Viewers have more control over lowering the volume of their listening devices (TVs, computers, cellphones) than they do over increasing them, when there is a high-end limit on how loud the device can push sound from its speakers.

All of this planning, testing, and rehearsing resulted in a successful show. It attracted a large, diverse audience spanning the UK, Germany, Australia, the U.S., and Canada. In fact, within Canada, there were live viewers as far east as New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the Magdalen Islands, and as far west as Alberta. Attendance by people outside of the Ottawa area would not have been possible with a live in-person show at a local venue. This demonstrates the unique value of a live stream show. Live streaming should be considered for the post-COVID future, in addition to in-person shows. Cuppa Joe is certainly open to hosting or participating in such events.

The show went well, starting on time and running uninterrupted. There was just one hitch, which is worth sharing for others to consider in their shows. Despite all the testing, some audience members found the audio level too low, early on in the show. It was an easy fix to increase it from our mixer. But since we hadn’t anticipated a situation like this, we were not 100% sure which controls impacted the digital feed to the live stream. And increasing the overall volume caused the sound levels from our monitor speakers in the performance space to be louder than we are accustomed, making it more difficult to sing in our nuanced way and to hear and blend with one another as well. So we needed to adjust that volume back down a bit after a couple of songs; and that seemed to work for everyone.

The learning for us is to make sure we have split the mixer outputs for the monitor speakers from the controls for the digital feed, so they can be controlled independently. We also need to do more sound-level testing before the show, to ensure that we start at a volume level that is on the high side rather than the low side. Viewers have more control over lowering the volume of their listening devices (TVs, computers, cellphones) than they do over increasing them, when there is a high-end limit on how loud the device can push sound from its speakers.

Acknowledgements

Chris Thompson provided excellent technical support in preparing for Cuppa Joe’s concert, and was always available as a sounding board. And thanks to Ian Schwartz for introducing the author to OBS.

Many thanks to Chris Thompson, Peter Feldman, and Linda Wilson for their reviews and valuable feedback on the drafts of this article.

Chris Thompson provided excellent technical support in preparing for Cuppa Joe’s concert, and was always available as a sounding board. And thanks to Ian Schwartz for introducing the author to OBS.

Many thanks to Chris Thompson, Peter Feldman, and Linda Wilson for their reviews and valuable feedback on the drafts of this article.

About the Author

John Wilson is a Professional Engineer who holds a BScEng in Electrical Engineering and an MSc(CS) in Computer Science. His musical background includes fifteen years of piano lessons starting at age five, singing in whatever school choirs and choruses were available to him, and playing trumpet for three years in the school band. He sang in a jazz choir prior to starting Cuppa Joe in 2008. John may be contacted about this article at [email protected].

John Wilson is a Professional Engineer who holds a BScEng in Electrical Engineering and an MSc(CS) in Computer Science. His musical background includes fifteen years of piano lessons starting at age five, singing in whatever school choirs and choruses were available to him, and playing trumpet for three years in the school band. He sang in a jazz choir prior to starting Cuppa Joe in 2008. John may be contacted about this article at [email protected].